An Index of Disobedience

BHARATHESH GD

14 August - 27 September 2025

Curated by Amshu Chukki

Artworks

Artworks

An Index of Disobedience

Curated by AMSHU CHUKKI

In a time when images are endlessly generated, manipulated, shared, and weaponised, the work of Bharathesh G D carves out a resistant, self-reflexive space—a site not of certainty, but of confrontation. His practice operates as an index of disobedience: not merely a poetic metaphor but a pointed method of resisting the institutional, aesthetic, and algorithmic frames that govern what images do and how they function. Through strategies of visual contradiction, recontextualization, and material friction, his work refuses inherited visual regimes, interrogates belief and perception, and exposes the sedimented violence that image cultures reproduce. Trained as both a painter and an art historian, Bharathesh’s work traverses painting, video, sound, sculpture, and conceptual practice. Yet, the material diversity of his work is unified by a persistent commitment to questioning how images mean, where they come from, and what they do. This inquiry is not merely aesthetic but historical, political, and deeply personal. Bharathesh’s visual grammar is shaped by his early life in Davangere, Karnataka—an economic centre from the 1950s through the 1980s—which emerged as a major industrial hub with its cotton mills, mill workers, cotton traders, and vibrant cinema culture. His father worked as a cinema cutout artist and projectionist, painting enormous film posters, obituary banners, and hand-lettered signs, often based on techniques inherited from the Baburao Painter school in Kolhapur. Baburao, a towering figure of early Indian visual modernity, moved fluidly between theatrical backdrops, painting, sculpture, and cinema—a lineage Bharathesh’s father continued, having trained at J.J. School and worked as an art director while in Bombay and briefly assisted V. Shantaram on the film Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baaje during his time there before he moved back to Davangere. Growing up around the Moti Theatre, where his father worked as a projectionist, Bharathesh absorbed the tactile infrastructures of image-making: paint, plywood, slide projectors, spools, the looping rhythm of celluloid film, and the ritual economy of cinema consumption. He assisted his father in painting backdrops, operated Westrex projectors, and made sandwich-glass slides for cinema ads—manual forms of storytelling that preceded the algorithmic saturation we now inhabit. It is this early immersion in analogue systems of spectacle, their economies and their intimacies, that continues to haunt and inform his current work. In his latest body of work, Pain Corporation of INDIA (2024–25), Bharathesh returns to the languages of signage and cinema cutouts made from plywood—yet with a destabilising force. The exhibition reads like a dismantled toolkit of instruction and indoctrination. Signs misfire—icons glitch. The viewer is never given a stable interpretive foothold. Pain Corporation of INDIA is not a declaration but a symptom—a way of making sense of the structural and psychic violence embedded in systems that parade as democratic. The overdose of democracy as spectacle, the erasure of dissent through amplification, the reduction of politics to branding. The large hybrid plywood cutouts, painted in bright poster tones and bordered with fluorescent yellows, parody film cutouts from Karnataka’s film poster and cut-out tradition, where large building-size cutouts of actors are propped up outside movie theatres and during political voting campaigns, where large painted cutouts of politicians are placed across the city. He draws from this iconography. In a brilliant gesture of critique, in 2015, actor-director Upendra released his film Uppi 2 with an upside-down cutout, mocking this very form and practice of ritualistic hero worship—denying it almost instantly through inversion and satire of the industry’s obsession with icon-making. Bharathesh’s works channel that same rebellious spirit: the cutout is no longer a hero; it is a sign in break-down. The artist describes these cutout compositions as “stacked narratives” or “meaning-making machines”—multi-layered constellations of images, symbols, and fragments that invite the eye to wander, pause, and form shifting associations. In IN and AS, Encrypted Forwards, layered forms draw on the Kannada phrase kuri galu saar kuri galu—“Sheep, Sir, Sheep”—immortalised in a 1960s poem by K.S. Nissar Ahmed as a sharp satire of herd mentality. In Ahmed’s verse, the voter is a sheep and the politician a shepherd, a metaphor that remains pointed today. This work is a nod to Francis Alÿs’s Cuentos Patrióticos (Patriotic Tales, 1997), where the artist leads a lone sheep around a flagpole in Mexico City’s Zócalo, gradually joined by more until a full flock encircles the national symbol. The piece recalls a moment from Mexico’s 1968 student protests, when the government organised a loyalty rally in the Zócalo. Instead of complying, many civil servants turned their backs on the stage and bleated like sheep, mocking the spectacle and refusing to be passive followers. In 32 Teeth and Extras, what appears at first as the boulder-strewn landscape of Hampi reveals itself, on closer inspection, as a wasteland of broken teeth. Drawing on his training as a landscape watercolourist and his repeated visits to Hampi, Bharathesh recasts the rocky terrain in bleached enamel forms incised with marks. Across this fractured expanse runs a Kannada phrase, delivered here as a WhatsApp message: “If you speak too much, I will break your teeth”—a common threat in street altercations. The teeth-as-boulders form a scarred anatomy, turning the landscape into a site of injury and aggression. In Louder than Silence: This Shall Pass Too, clusters of eyes emerge from grotesque, exposed flesh. Following the shifting gaze leads to a knot of clouded, lifeless eyes. The work recalls the cinematic symbolism of Hitchcock, who used the eye to probe voyeurism and the fragility of perception, and Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, where the eye becomes a tool of behavioural control. Bharathesh’s version merges these legacies into a vision where the eye is at once vigilant and decaying—an organ of both surveillance and its own erosion. The works in this series lean into a fleshy grotesque: anatomical, visceral, and designed to unsettle. A key work, Too Much Democracy…, presents a tableau of tiny cast relief objects/logos, their slogans and symbols both hyper-legible and deeply opaque. Here, Bharathesh’s recent use of hand-painted dental plaster reliefs, displayed in hanging plastic at local kirana shops-style pouches—drawn from his childhood memory of a kirana store his family opened and still runs in Davangere—also returns us to the vernacular economies of image-making. These works are intimate and mass-produced, devotional and disposable, suspended between the sacred and the synthetic. Symbols like police barricades, JCBs, voting-marked fingers, Swachh Bharat logos, and mutated icons become tokens in a new economy of state power. In an era of fake news, AI hallucinations, and deepfake videos and AI-manipulated speeches used for political propaganda, his return to painting becomes a form of refusal—a refusal to outsource meaning to algorithms. In a world flooded with simulation, painting becomes an analogue counterattack. It slows down the eye. This work is not nostalgic. It is speculative. Bharathesh isn’t mourning a lost era of cinema aesthetics or artisanal labour. Rather, he is repurposing its techniques to ask urgent questions about truth, violence, attention, and memory. His political critique does not scream; it leaks, seduces, glitches, and folds. The past decade has witnessed the rise of AI-generated propaganda, fabricated spectacle, and a saturation of political mythologies across social media. AI-generated images of Prime Minister Modi as Bhishma Pitamah or saffron superheroes are not innocent aesthetics—they are instruments of myth-making, meticulously constructed to evoke divine authority and moral infallibility. These images do not merely circulate—they are engineered to go viral, operating through the emotional and algorithmic economies of digital media. From Modi’s 2014 election campaign that used holograms to simulate omnipresence, to the 2024 Instagram campaigns that used Midjourney to generate fantastical depictions of him as mythic warriors, the strategic deployment of synthetic imagery has violated even platform rules requiring transparency around AI-generated media. At the same time, deepfakes of politicians, fabricated crowd images at rallies, and AI-resurrected avatars of deceased leaders like Karunanidhi—used to simulate speeches in Tamil Nadu—proliferated during elections across South Asia. In Bangladesh, pro-government accounts circulated deepfake videos targeting opposition leaders, while in Pakistan, AI-generated audio speeches allowed imprisoned politicians like Imran Khan to appear virtually at rallies. Fact-checkers struggle to keep pace as meme factories, sponsored influencers, and manipulated news broadcasts construct parallel realities in real time. These tactics were also evident during the CAA-NRC protests, when manipulated images and incendiary videos sought to delegitimize dissent; during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, when the Tablighi Jamaat was falsely blamed for viral spread through coordinated misinformation campaigns; and in the tragic months of lockdown when visuals of barefoot migrant workers walking hundreds of kilometers became viral symbols of abandonment—quickly politicized, memefied, or even erased by official narratives. These moments reveal not only the volatility of the visual field but its capacity to weaponise emotion and manufacture affective consensus through repetition, spectacle, and erasure. In Bharathesh’s work, these fragments—deepfakes, campaign slogans, mythic portraits, bureaucratic logos—appear in mutated form. Reassembled into hybrid beings—part machine, part icon, part wound—they resist coherence. His configurations do not narrate—they accrete, like sediment, forming an unstable index of our fractured image environment. In many ways, Bharathesh’s works function as a living archive—not just of state violence or fake news, but of his own lineage, the embodied histories of cinema labour, and the micro-economies of image-making in small towns like Davangere. His father's legacy—painting cutouts, running projectors, making obituary posters—is not background. It is part of the central nervous system of the work. From this comes his intimacy with the infrastructure of spectacle: what a reel contains, what a splice means, how light meets emulsion. Seen in light of M.M. Kalburgi’s belief that images and rituals must be interrogated rather than venerated, Bharathesh’s own aesthetic and conceptual refusal takes on a potent political valence. Kalburgi’s refusal to accept the Bhagavad Gita as his religious text—insisting instead on the vachanas—alongside his rejection of idol worship, celebration of Ganesh Chaturthi by Lingayats, and his insistence on distinguishing Lingayatism from Hinduism, were not iconoclastic for provocation’s sake—but acts of intellectual rigor, grounded in historical materialism. In a similar spirit, Bharathesh does not abandon faith but interrogates it. His long-form video work, GOD Conditions Apply, examines the spectacle of bodily belief, how difference is rendered divine or deviant depending on its usefulness to power. He charts how anomalous bodies are mythologised, worshipped, or disfigured by the gaze. His gaze, however, is not anthropological—it is intimate, fractured, and deliberately unresolved. An Index of Disobedience is thus not just a title. It is a methodological proposition. It suggests that the image can disobey—that it can refuse to be decoded, circulated, or weaponised. In the cutouts, the stacked narratives, the layered signs and shifting associations, this refusal takes form—images that act not as singular truths but as restless, recombining fields. Painting, even today, can be a site of conceptual resistance. Art can mourn and mock, testify and unravel. In an age where violence is aestheticised and truth is a matter of algorithmic consensus, Bharathesh G D’s work invites us to look again—not for clarity, but for contradiction. To read the signs not for what they claim, but for what they conceal. To enter the noise of our moment, and instead of being silenced or seduced by it, to learn to listen differently. Amshu Chukki

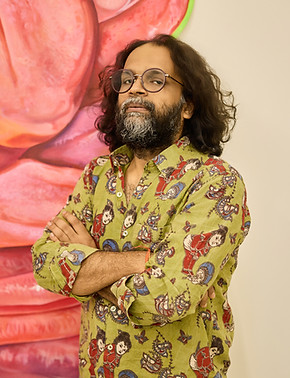

Bharathesh GD

Bharathesh GD is a Bangalore-based artist, curator, researcher, and educator whose practice moves across painting, video, sound, installation, photography, and performative objects. With a background in both studio-based painting and art historical research (BFA, Government College of Fine Arts, Dharwad; MVA in Art History, Karnataka Chitrakala Parishath), Bharathesh’s multidisciplinary approach interrogates abstraction, belief, and image-making through shifting constellations of form and thought.

Over the past two decades, his work has explored the politics of perception and the affective power of signs, often engaging non-linear narratives and ephemeral material processes. His long-term projects—such as GOD Conditions Apply, Sound Signatures, and the recent Pain Corporation of INDIA (2024–25)—dissect the visual languages of divinity, democracy, and dissent, staging installations that operate as both meaning machines and critiques of symbolic violence.

He has exhibited widely in India and internationally, including at the Indian Art Fair (2024), Serendipity Arts Festival, gallery Espace, Stadtgalerie Bern (Switzerland), and Theertha Red Dot Gallery (Colombo). His teaching spans over a decade across leading architecture and design schools in Bangalore. Bharathesh’s practice is marked by a deep commitment to process, pedagogy, and the unstable relationship between image, memory, and political imagination.

Amshu Chukki

Amshu Chukki is a multidisciplinary artist based in Bengaluru, India. His site-informed practice explores new ways of articulating landscapes and urban environments, attending to the visible and not-so-visible interconnections between life, cinema, urbanity, infrastructure, politics, and fiction. In his work, the landscape becomes a field of inquiry—where various communities and their idiosyncrasies come together, initiating conversations from localized micro-contexts that expand outward to broader narratives.

The various textures of material and location in his work come together to overlap in conversation with history, fantasy, site, and resistance. His experimental films often spill out into drawings, sculptures, and installations that attempt to stage the city as a protagonist.

Chukki holds a postgraduate degree from the M.S. University of Baroda. His recent solo exhibition, Different Danny and Other Stories, was held at Chatterjee & Lal, Mumbai, in 2022. He has participated in several group exhibitions and screenings, including Visualising African-Asian Worlds, NYUAD, Abu Dhabi (2024); Cloak and Dagger: India’s Fictional Times, Zuzeum Art Centre, Riga, Latvia (2021); From Cinema, AI(R)C Artists in Revolution Collective, Los Angeles (2021); Chennai Photo Biennale (2018); TURN OF THE TIDE – 20/20 Artists for KHOJ, New Delhi (2018); Asia Film Focus: Time Machine, Objectifs Centre for Photography and Film, Singapore (2017); and India: Maximum City, St. Moritz Art Masters, Switzerland.

He has been awarded international residencies including the St. Moritz Art Academy, Switzerland (2022); The Darling Foundry – India–Québec Residency, Montreal, Canada (2015); and Coriolis Effect: Currents across India and Africa at KHOJ, New Delhi (2015). Chukki is a recipient of the Space Studio Artist’s Grant (2021), the Forbes 30 Under 30 recognition for Visual Arts (2016), and the INLAKS Fine Arts Award (2014).